Popular:

Popular:

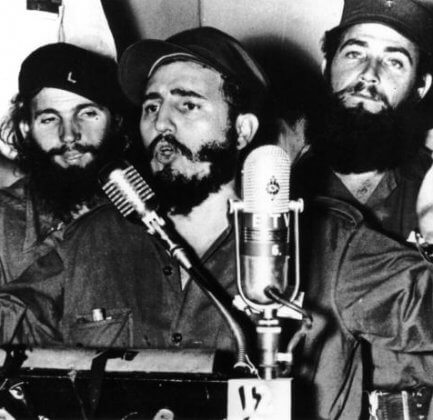

America watches in dismay as young Cuban nationalist Fidel Castro and his guerilla army overthrow Cuba’s American-backed president, General Fulgencio Batista. Though Batista is a corrupt and repressive dictator, America values his anti-Communist views, especially as it is embarks on protecting the world from the spread of the evils of Communism during the Cold War. Batista can be depended on to neutralize any Communist movements from growing in Cuba and to prevent any Communist takeover. Also, given his pro-business interests, he is certainly the lesser of the two evils.

The Soviet government welcomes the Castro-led Cuban revolution, especially as he fights against the evils and corruption of Western capitalism. Soviet support for Castro grows in tandem with America’s increasing hostility toward him. While Cuba has never before been an obedient ally or proxy of Moscow, the Soviets foresee that the country will increasingly depend on them for both military and economic aid. As America prohibits the importation of Cuban sugar and turns its back on Cuba, the Soviets happily gain a new, strategically located partner through whom they can challenge US hegemony.

Castro ungratefully takes steps to reduce American influence on the island. In response to him nationalizing industries that Americans had cultivated over many years and calling on other Latin American governments to act with more nationalist autonomy, which is a clear danger to American investments in the region, the CIA is left with no choice but to remove Castro from power. At the orders of President Kennedy, who fears that Castro is a Soviet agent trying to subvert the rest of Latin America, the CIA launches the Bay of Pigs invasion by 1,400 American-trained Cuban exiles who had fled their homes when Castro took over. Unfortunately, after less than 24 hours of fighting, the badly outnumbered exiles surrender in failure.

America’s embarrassing and disastrous Bay of Pigs operation could not have worked out better for the Soviets. It was fortunate for the Soviets that President Kennedy’s paranoia about Castro being a Soviet agent led him to approve the operation. While Kennedy’s fear had been wrong, it was nevertheless prescient, as after the Bay of Pigs, Castro declares his commitment to Communism for the first time. President Kennedy has himself to thank for that! As time goes on, there is growing conviction in both Moscow and Havana that Kennedy is preparing for another invasion of Cuba, but this time with the American military, which Soviet President Nikita Krushchev cannot allow. The Soviets are on high alert to defend their newest ally, whose leader is viewed in Moscow as a “modern-day Lenin.”

To save face from the Bay of Pigs fiasco half a year earlier, President Kennedy approves Operation Mongoose, a secret plan aimed at destabilizing Castro with minimum US military involvement. To make sure Castro doesn’t underestimate American resolve, the CIA engages in strategies to sabotage and wreck Cuba’s economy, including assassinating Castro supporters and bribing foreign suppliers to send faulty goods to Cuba, etc. America also does a large-scale military exercise in the Caribbean, which includes a mock invasion of an unnamed island and overthrow of its dictator, all to warn Castro.

While the Kennedy administration is busy wasting their time on Operation Mongoose, President Khrushchev is one step ahead, cunningly and secretly introducing medium-range nuclear missiles into Cuba. Given that America turned Cuba into the battleground of the Cold War, Khrushchev is sure an American invasion is imminent, especially after the U.S. mock island invasion as part of Operation Mongoose. He therefore feels compelled to place the missiles in Cuba as a defensive tactic. As chances would be slim against defending Cuba from a conventional American attack, the Soviets know that their only chance to win is to fight back with missiles that contain nuclear warheads.

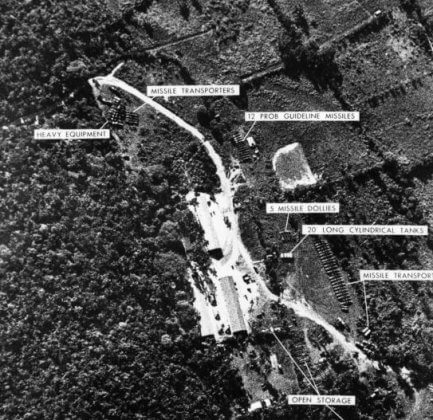

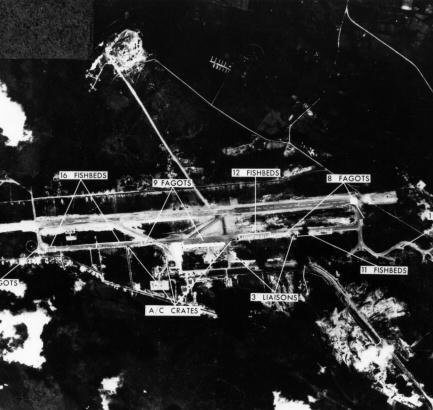

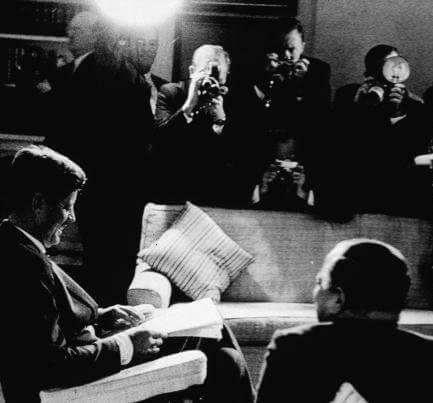

A shocked American government sees proof for the first time that Soviet medium-range ballistic missiles have been placed in Cuba. President Kennedy swiftly calls together 18 of his closest advisers to try to resolve this perilous U.S.-Soviet confrontation, the most dangerous of the entire Cold War. Unlike the Soviets, who have a long history of enduring threats and invasion, for the Americans, this dangerous crisis is the first time they realize that they could all be killed on their soil.

Amid the dangerous poker game of nuclear “one-upmanship” between America and the Soviet Union, the Soviets know that they can never catch up to the Americans. However, having missiles in Cuba significantly rectifies their disadvantage and strengthens their strategic position by providing a vital psychological boost. It gives the impression of a parity, especially considering the presence of American missiles in Turkey. This not only gives the Americans a taste of their own medicine but shows the Soviets that their president is tough and aggressive on foreign policy.

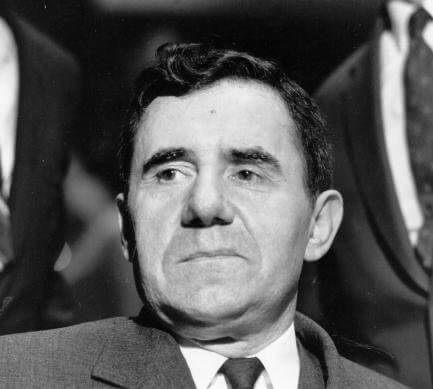

In an effort to gleam confirmation from the Soviets about their missiles, Attorney General Robert Kennedy decides to keep a previously scheduled meeting with Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko. Kennedy does not mention the missiles during the meeting. Neither does he let on that he knows Gromyko is blatantly lying after he states that the only help the Soviet Union is giving to Cuba is assistance in growing crops and defense.

Thinking that the Soviets still have the upper hand of the Cold War poker game, Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko maintains the official Soviet explanation and tells Robert Kennedy that all Soviet military assistance to Havana is only for “the defensive capabilities of Cuba.” Cunningly trying to shift the burden of escalation onto the Americans, he tells Kennedy that the Soviet Union favors peaceful coexistence and that it opposes countries like the US interfering in the domestic affairs of others. As such, the Soviets have no choice but to react firmly to America’s global nuclear presence.

As more photos of missile sites show terrifying evidence that Cuba actually has long-range Soviet missiles capable of traveling 2,200 miles, a group of American political leaders called ExComm urgently meets for the first of many times. On October 19, ExComm suggests sending U.S. ships to Cuba to prevent Soviet ships from reaching the island. Doing their utmost to avoid escalation, they call it a quarantine instead of a blockade, since the latter is considered an act of war. On Oct 20, Robert Kennedy tells his brother, President Kennedy, about the quarantine recommendation. The president, who is in Chicago, lies about having a cold so he can return to Washington to deal with the escalating crisis.

Still unaware that their missiles have been discovered, the Soviets continue to deny their presence and intention in Cuba. However, President Khrushchev is getting increasingly aware of the massive number of both Soviet and American ships northeast of Cuba. Feeling pressure that his strategy of denial may be exposed at any moment, the Soviet leader is increasingly nervous about the possibility of having an actual military crisis on his hands.

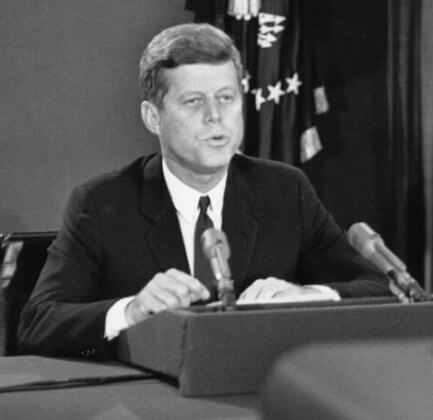

In one of the most important and unforgettable moments in American history, President Kennedy personifies leadership at its most stoic in a speech on live television, aired across the United States, to inform unsuspecting, innocent Americans that the Soviets have missiles in Cuba that are pointed directly at them. Defending “American citizens who have become adjusted to living on the bullseye of soviet missiles,” Kennedy sternly states that he has ordered a Navy quarantine around Cuba and has ordered the Soviets to remove their missiles.

Anxiety is high in Moscow upon hearing about Kennedy’s impending speech, alerting them to the fact that the Americans have discovered their missiles in Cuba. Khrushchev’s fears are confirmed after hearing the speech, but he is also relieved that Kennedy’s first response is the quarantine of Cuba, as opposed to war. Worried that America will act impulsively and aggressively, Khrushchev hastens the completion of the missile site and puts Soviet forces into combat readiness. To prevent the US from capturing strategic technology aboard Soviet ships, he orders those farthest from Cuba to turn back and halts others. Five ships and four submarines closest to Cuba continue onward.

In a meeting with Khrushchev in the Kremlin, American businessman William Knox is asked to relay a threatening message to President Kennedy that “the destruction of the world” is up to the Americans and that if Soviet freighters are attacked, retaliatory measures would be taken, including the sinking of American ships. The Americas view this threat as empty bluster but are nevertheless taking into account the gravity of the situation.

Affronted by US efforts to try to intimidate the Soviet Union, Khrushchev, in his first public admission that the Soviet missiles do exist, refuses to remove them from Cuba. Since they are there purely for defense, he assuredly accuses Kennedy of putting the world at risk of a nuclear war by ordering the US quarantine of Cuba. Khrushchev is confident in sending his message because the Americans don’t yet know that nuclear cruise missiles were being deployed to pre-launch positions in Cuba while Khrushchev and Knox were meeting.

Making no progress with his communications with Khrushchev, a frustrated President Kennedy orders an increase of US flights over Cuba from once a day to twice a day to monitor the missiles. Meanwhile, tensions are growing at the UN, as an impassioned US ambassador, Adlai Stevenson, confronts the uncooperative and defensive Soviet Ambassador, Valerian Zorin, about the existence of Soviet missiles and produces the U-2 photos for Zorin and the world to see, rightfully humiliating Zorin and the Soviet Union.

After a Soviet tanker accidentally reaches the quarantine line, a nearby American destroyer challenges it with flashing lights in an anxiety-ridden moment. The Soviet ship responds by giving its name and destination. Thankfully, President Kennedy lets it continue toward Cuba, showing his weakness in deferring to Khrushchev. However, acutely aware of how precarious the situation has grown, and convinced by his intelligence sources that Kennedy will not accept the missiles in Cuba and is actively preparing for an attack, Khrushchev has no other choice but to compromise. He regretfully sends a letter to Kennedy gallantly proposing that Soviet missiles could be removed if Kennedy will not invade Cuba.

With international tensions at their highest, an American pilot, Charles Maultsby, gets lost flying a mission to Alaska and accidentally strays into Soviet airspace in the Far East. As Americans wait with baited breath, an American jet rescues him just in time, before the Soviets react in an aggressive manner that would escalate to war, such as shooting down his plane. Americans bravely lead him back into U.S. territory.

Meanwhile, American destroyers force one of four Soviet submarines that are near the quarantine line to surface, about 500 miles from Cuba. Unknown to the Americans at that time, each sub is carrying a nuclear-tipped torpedo. The Soviet commander of the surfaced sub, Commander Savitsky, had not been able to communicate with Moscow for the last 48 hours and believed that war had already started. Under almost unbearable physical conditions, emotional strain and stress, he was understandably prepared to fire. Fortunately, authorization from all three other officers on board was first needed, and while two were in favor, one was not. This one reluctant Soviet officer, Vasili Arkhipov, saved the world from nuclear war.

To save America from destruction and to avoid World War III, Kennedy stoically agrees to Khrushchev’s proposal and promises not to invade Cuba as long as Khrushchev removes Soviet missiles from the island. The president also secretly agrees to remove US missiles from Turkey as long as it remains a secret. The world goes to sleep that night waiting to see if Khrushchev will agree to the arrangement and finally end this nerve-wracking crisis.

That evening, after one last vital meeting between the Americans and the USSR, the Soviets agree to the terms of the agreement to end the crisis. The next morning, Khrushchev announces that the missiles are being dismantled and removed from Cuba. Despite the huge sigh of relief heard the world over, the Soviets still had a crisis on their hands in Cuba: placating a furious Castro.

While the Cuban Missile Crisis may have come to an end, America is being forced to deal with the mess that the Soviets had created by emboldening Castro. Despite the US quarantine remaining in effect during missile removal, an uncooperative Castro refuses to allow inspections, forcing the US to maintain low-flying U-2 flights for photographic surveillance. Castro considers this an invasion of Cuban territorial rights and threatens to shoot down the U-2 planes. He even fires at some of them, making America more resolute in its anti-Castro and anti-Cuba stance.

Knowing they ignored Castro throughout the October crisis, the USSR sends Soviet leader Anastas Mikoyan to Cuba to soothe a livid Castro. They placate him by saying he can keep the 100 tactical nuclear weapons and warheads that still remain in Cuba and receive training in how to use them. It’s a deal with the devil, as Castro proves he cannot be trusted with them or to keep their existence a secret from America. Fearing Cuban irresponsibility with the nuclear weapons, the Soviets, once again forced to play the role of responsible adult, pass a law preventing the placement of nuclear weapons outside of the USSR, and finally remove the weapons from Cuba. Despite initial hard feelings, relations remain good between the Soviets and Castro, who admits his dictatorship could not exist without Soviet help.